(Teksti suomeksi löytyy blogin lopusta)

Personally, I have only faint recollections of that day. Only a vague, blurry picture comes to mind: a grey tin dish bowl full of flopping, silvery, freshly caught fish. You could reel in as big catches from the River Kemijoki as you ever wanted.

In my adult years, I have heard a bit more about the events of that April Sunday morning:

– We caught some graylings! Look! An entire bowlful of them..!

The hallway had echoed with the cries of my primary school-aged brother and the five-year-old me. We had chucked our wet mittens and beanies on the floor and hauled in the catch in a heaped bowl for others to see.

Once our accomplishments of that morning had been sufficiently marvelled, Mum began to clean the catch. Meanwhile, we hungry fishers scooped up rice gruel and crispbread into our pie holes and went through the riverside events once more.

– We managed to get on one of them big chunks of ice by Ampukallio and drop the jig into the water. Kaisa caught a grayling first, and then they kept coming and coming.

– Yes, and I caught the biggest one!

– Let’s eat up and go back!

– Will you take me along?

After having finished our meal, we had returned to the banks of River Kemijoki. However, what awaited us was a big disappointment! The chunk of ice on which we had ice fished all morning had disappeared during our meal break. As it rose, the flood water had snatched it away and sunk in the foams of the rapids.

Thereafter, going down to the river front had been strictly forbidden for us children. Nevertheless, we still went there sometimes to take a little look.

***

In my family, catching graylings in the main stream of River Kemijoki in April was the highlight of the early-year fishing season. The next fishing season was in early June, soon after the lakes had thawed. That’s when we went spawn-fishing for pike in the wilderness lake, and Dad took us kids to the wilderness for several days to fish.

Traditional fishing area of my family in Finnish Lapland.

We would spend days on end on those trips, with the intention to catch and bring home loads of fresh fish. As the evening fell, we threw long strings of nets from the shallow shores towards the deep waters, and sat down by the fire to wait for the pike to fall for our trap.

Spawn-season fishing, particularly for some species of fish, such as pike and perch, is a tradition that has continued in Finland since prehistoric times, and it has been practised for its productivity1. In other words, well-timed fishing allowed for obtaining abundant catches.

As permanent settlement spread across Lapland in the early 19th century, remote fishing in the wilderness began to wane. In my family, however, this ancient tradition has been kept alive, even by my own generation.

Perhaps one reason why we still practised spawn-season fishing was that after a long winter, freshly caught fish simply tasted so incredibly delicious. It added variety to a diet filled with game meat and grains. I vividly remember my parents sitting at the kitchen table, enjoying the first fresh fish after the winter. The mood was quiet, grateful, almost solemn!

The second time of the year to head out to a wilderness lake for fishing was July. We were able to spare the time for it after hay making and before cloudberry picking. All of us kids who were strong enough to wade several kilometres through dense forest would join Dad on these trips.

A fishing net woven from linen string. Stones covered with birch bark act as sinkers.

Rovaniemi Local History Museum.

Fishing around mid-summer also centred around net fishing, but for a little girl like me, fishing with rod and line and using worm as a bait was the thing, as you could catch perch and roach almost nonstop. As fishing skills developed, it was time to take up the spinning rod with a lure, which meant that the size of one’s personal catches increased considerably. My father often caught the largest, over five-kilo pike, using pike traps. It is an effective device, the setting of which was fun to watch, but only from a safe distance.

Besides grayling, pike and perch, in the summer we would fish for river trout from the little brooks that flow into the River Kemijoki. Also, in the autumn, we would hike to wilderness ponds to catch whitefish.

Salmon, the great storyteller

My father’s memoir also reveals that my family used to have two traditional wooden shore weirs in the River Kemijoki before it was dammed, which we would check every morning and night, catching grayling, pike and trout. Salmon was fished using nets and by trolling. Our largest salmon ever weighed a whopping 18 kilos.

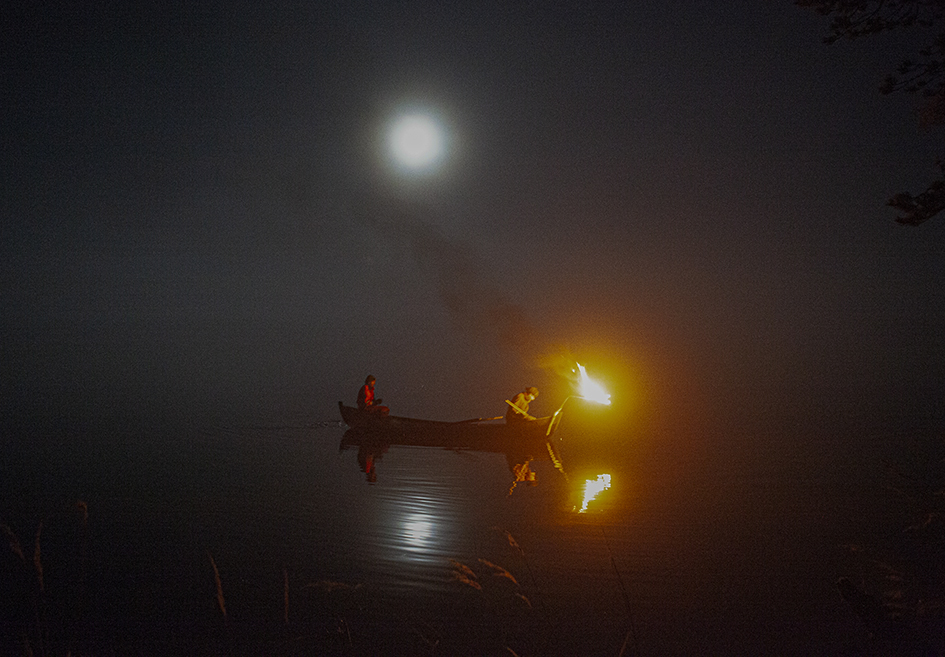

Torchlight fishing at night on River Iijoki. Photo©Janne Körkkö.

We caught salmon also by torchlight fishing in the dark autumn nights. It’s where the fisher tries to find fish near the shore with the help of a fire lighted in the bow of the boat, and then spears them with a long-handled gig2. Despite the fact that the use of spears was forbidden in the 1902 Fishing Rule3, it is said that they were still used for fishing in the River Kemijoki after that. -It sure was exciting, my Grandfather had once exclaimed, they say. No wonder he did, as the fisher coming ashore could be met in the dark by the police with pistols drawn. (The ban of using long-handled gig was repealed in 1952).

I don’t have personal experiences of salmon fishing, but salmon has always been present in the stories as described above. The ascent of migratory fish to our home river came to an end when the Isohaara hydroelectric dam was built in 1949. I grieve the salmon’s fate, and I feel its loss particularly when I visit River Tornionjoki, where this king of the river can still be seen.

Jaakko Heikkilä is fishing King salmon with traditional dipnet in River Torniojoki. Photo©Antti Ylönen.

It is quite evident that the life of my family very much revolved around fishing. Making, maintaining and setting fishing gear, checking them and handling the catch has been a big part of our daily lives. As a livelihood, this was called household fishing, which means fishing where the catch was consumed within the fisher’s own household and which was elemental to the family’s subsistence. There was plenty of fish to feed the family, and from time to time, there was enough for some of it to be sold, even.

The dispute over the ownership of salmon, in other words, who has the right to catch salmon, has continued since the Middle Ages, when Finland was part of the Kingdom of Sweden. Today, the different angles in the lively debate can be followed on social media, too. Since there is so much confusion and ambiguity over this issue, in 2019, The Finnish Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry prepared a report discussing the royal salmon prerogative, which refers to the exclusive right of the State to fish for salmon in Northern Finland, and the preconditions for it to waive this right in the future4.

In my opinion, this report provides good food for thought in continuing the ongoing discussion about the future of salmon. What is particularly remarkable about the report is that even the state is capable of reflection, in this case from the legal-historical perspective, thereby expressing its willingness to assess the weight of its own actions as well as change needs.

I find the ownership of salmon and the financial gain it entails of secondary importance – whether the salmon belongs to the Forest Sámi people that has been living in that area, or to the peasants that owned the land later, or to the fishers who had private shore weirs and nets there, or to the state – when the primary concern should be the intrinsic value of the salmon and other fish fauna and biodiversity. Besides the value of use, also the value of existence should be considered when making political decisions, so that the survival of the species and their habitats could be secured as well as possible.

An interesting perspective on the political aspect of the salmon is introduced by Ville-Aarne Nordberg in his recent social science study where he analyses the significance of the salmon as the builder of a political and regional identity5. Referring to the interviews he conducted in the Tornio-Muonio river valley, Nordberg finds that the salmon and salmon fishing reinforced the formation of both regional and political identities. ’They, in turn, lead to various means of influencing and aspirations, and also form an understanding of one’s own setting and its differences to other regions.’

Local people are ice fishing on Lake Simojärvi in Finnish Lapland.

I, for my part, have received my heritage of the River Kemijoki salmon and salmon fishing in an immaterial form, in the form of numerous stories that have been passed on in our family from generation to generation. These stories are living cultural heritage, the kind of material that can be looked into without being primarily concerned with political, financial or ownership-related aspects.

According to environmental sociologist Outi Autti6, the stories about the salmon have played a pivotal role in the fishing culture around the major northern rivers: the locals observed and learnt about the salmon’s behaviour while fishing and interpreted and compared the stories and observations with their own lives. And ’the salmon shaped the salmon fishing identity of the riverside communities, and even the idea that individual people had of themselves. The salmon had a fundamental effect on the people’s and families’ ways of being, traditions and sense of belonging.’

Fish weir and traps in Taivalkoski in 1910. Photographer T.H.Järvi. National Board of Antiquities.

In other words, storytelling plays a central role here. Margaret Atwood refers to a theory according to which the earliest form of story is a story about a trip between the here and now reality – where both the storyteller and the audience exist – and another dimension, which can be the past or the world of our ancestors or those who have passed on7.

Atwood believes that it is through art and stories that the human species has managed to survive from the dawn of time to where we are now; that as a species, we have developed the ability to adapt over a very long period of time during which the hunting and gathering cultures of the pleistocene epoch thrived. Stories helped humans to survive, otherwise the ability to create and communicate a story would have disappeared during our evolution.

The following little trip between the dimensions of two realities took place in our family in the 1920’s. This is a story from the River Kemijoki as told by my father, Veikko Kerätär, and recorded by my sister Outi Autti when she was conducting an interview survey:

“Grandpa had gone off to pay a short visit to Autti, but for some reason or other he’d had to stay overnight. And upon leaving, he’d told Dad to check the nets in the morning. So he did. He’d gone to the river and found two salmon. I guess Dad was still a bachelor then and reckoned he needed some money and decided to sell the other salmon without telling Grandpa. But Grandpa had come back from Autti and asked about the catch – There was only one salmon? – Not two?! – Should have been.. Last night there were two men I fought with in my dream..”

‘Kojamo / Buck salmon’. 15 meters long and 3,5 meters high fish shape that has a cathedral-like space to step inside. The sculpture is by artists Teija and Pekka Isorättyä, commissioned by City of Tornio in 2021. Photo©Antti Ylönen.

Sources:

1 Puukoukusta trooliin -suomalaisen kalastuksen 10 000 vuotta.

2 Pure magic – torchlight fishing

3 Kalastussääntö Suomen suuriruhtinaanmaalle.

6 The wise salmon that returned back home.

7 Margaret Atwood on literature and environment.

Text ©Kaisa Kerätär

Photos by Kaisa Kerätär if not mentioned otherwise.

Translation by NorthLing.

ELOONJÄÄMISTARINAT

Itse muistan siitä hommasta vähänlaisesti. Vain epämääräinen, häilyvä kuva nousee mieleen: harmaa peltinen tiskivati täynnä sätkiviä, hopeankiiltäviä, juuri pyydettyjä kaloja. Saalista niin paljon kuin kerkesi nostaa Kemijoesta.

Aikuisiällä kuulin hieman lisää tuon huhtikuisen pyhäaamun tapahtumista:

– Saatiin harreja! Kattokaa! Koko maljan täydeltä..!

Alakouluikäisen veljeni ja minun, viisivuotiaan, kiljaisut olivat kaikuneet eteisestä. Märät vanttuut ja pipot olivat lentäneet kaaressa lattialle, ja kalansaalis kuljetettu kukkuraisessa astiassa muiden nähtäville.

Aamuisen työmme tuloksia ihasteltiin, ja äiti alkoi perkata ja puhdistaa saalista. Sillä välin me nälkäiset kalastajat kauhoimme riisivelliä ja näkkileipää suuhun, ja kertasimme samalla jokirannan tapahtumia.

– Me päästiin semmoselle isolle jäätelille siinä Ampukallion kohala, siitä ylsi laskemaan pilkin veteen. Kaisa sai ekana harrin, ja sitte niitä alko tulla yhtenään.

– Nii, ja miäpä sain sen isoimman!

– Syyään pian ja lähetään uuestaan!

– Otakko taas minukki mukhan?

Ruokailun jälkeen olimme palanneet takaisin Kemijoelle, mutta pettymys olikin suuri! Jääteli, jolla olimme koko aamupäivän pilkkineet harjuksia, oli ruokatauon aikana kadonnut. Tulvavesi oli noustessaan napannut sen mukaansa, ja upottanut kosken kuohuihin.

Sittemmin joen rantaan meneminen oli meiltä lapsilta lujasti kielletty. Vaikka tulihan siellä silti käytyä kurkistelemassa.

***

Huhtikuinen harjuksenpyynti Kemijoen pääuomassa oli perheemme kalastuskauden alkuvuoden kohokohta. Seuraava kalastussesonki oli kesäkuun alkupuolella, pian jäiden lähdettyä järvistä, jolloin vuorossa oli hauen kutupyynti erämaalammella. Tuolloin isä yhdessä lapsikatraan kanssa siirtyi useaksi päiväksi kaukokalaan.

Matkoineen nuo retket kestivät useita päiviä, ja tarkoitus oli saada iso määrä verestä eli tuoretta kalaa kotiin viemiseksi. Laskimme iltasella useita, pitkiä verkkojatoja rantamatalasta kohti syvänteitä, ja jäimme nuotiotulen äärelle odottamaan, alkaisivatko hauet ’jutkahdella’ pyydyksiin.

Kutupyynti eli perinne joidenkin kalalajien, etenkin hauen ja ahvenen, lisääntymisaikaiseen pyyntiin on jatkunut Suomessa esihistorialliselta ajalta saakka, ja sitä on harjoitettu sen tuottavuuden takia1. Eli oikeaan ajanjaksoon ajoitetulla pyynnillä on kyetty saamaan maksimaalinen saalis.

Erämaihin suuntautunut kaukokalastus vähentyi Lapissa pysyvän asutuksen levitessä, 1800-luvulle tultaessa. Omassa perheessäni tuo ikiaikainen perinne on jatkunut kuitenkin pitkään, aina omaan sukupolveeni saakka.

Kutupyynnin jatkumista selittää meillä ehkä se, että tuore vastapyydetty kala maistui mahdottoman hyvältä pitkän talven jälkeen. Saatiin vaihtelua riistaliha- ja viljapainotteiseen ruokavalioomme. Muistan omat vanhempani heidän istuessaan keittiössä syömässä ensimmäisiä tuoreita kaloja talven jälkeen. Tunnelma oli hiljainen, kiitollinen ja lähes harras!

Heinäkuussa oli toinen ajankohta lähteä erämaajärvelle kalanpyyntiin. Heinänteon ja hillanpoiminnan välissä siihen oli sopivasti luppoaikaa. Isän mukana kairaan vyösysivät lapsista kaikki ne, jotka ’kynnelle kykenivät’ eli jaksoivat pontevasti kävellä usean kilometrin matkan umpimetsässä.

Myös keskikesän pyynnissä verkkokalastus oli tärkeässä roolissa, mutta itseni eli pienen tytön kannalta mato-onkiminen oli kiinnostavinta, siinä kun sai nostaa ahventa ja särkeä rannalle solkenaan. Kalastustaitojen kartuttua oli vuorossa virvelin eli heittovavan käyttö, jolloin henkilökohtaisten saaliskalojen koko kasvoi tuntuvasti. Suurimmat, yli viisi kiloa painavat hauet isäni sai usein iskukoukuilla. Se oli julma pyydys, jonka virittämistä oli mukava katsoa, mutta jota ei tehnyt mieli mennä itse sormeilemaan.

Harjusten, haukien ja ahventen lisäksi kotitarpeiksi kalastettiin kesäisin purotaimenta Kemijokeen laskevista pikku puroista. Lisäksi kävimme syksyisin erämaalammilla kalastamassa siikoja.

Lohi, tuo suuri tarinankertoja

Isäni muistelmista selviää myös, että perheelläni oli Kemijoessa ennen sen patoamista kaksi rantapatoa, joita käytiin aamuin illoin kokemassa saaden harjusta, haukea ja taimenta. Lohta pyydettiin verkoilla ja uistelemalla, suurimman lohen ollessa 18 kiloinen.

Lohta on pyydetty meillä myös tuohustamalla (tuulastamalla) pimeinä syysiltoina. Siinä kalastaja koettaa löytää rantavedessä olevia kaloja veneen keulaosaan sytytetyn tulen avulla, ja saalistaa niitä iskemällä pitkävartisella atraimella. Vaikka atrainten käyttö kiellettiin vuoden 1902 kalastussäännössä2, kerrotaan niillä pyydetyn Kemijoella sen jälkeenkin. -Oli se jännää hommaa, oli äiji (isoisä) joskus todennut. Rantautuvaa kalastajaa kun saattoi syksypimeässä olla odottamassa poliisit pistooleineen. (Atraimen käyttökielto poistettiin kalastuslaista vuonna 1952).

Itselläni ei ole lohenkalastukseen liittyviä kokemuksia, mutta lohi on ollut aina läsnä edellä kuvatun kaltaisissa tarinoissa. Vaelluskalojen nousu kotijokeemme loppui vuonna 1949 Isohaaran voimalaitospadon rakentamiseen. Suren lohen kohtaloa, ja sen menetys tuntuu erityisen vahvana vieraillessani Tornionjoella, jossa tuota joen kuningasta voi yhä päästä ihastelemaan.

Perheeni elämä perustui siis hyvin vahvasti kalastukseen. Pyyntivälineiden rakentelu, huolto ja pyyntiin virittäminen sekä pyydysten kokeminen ja saaliin käsittely on ollut päivittäistä puuhaa. Elinkeinona tästä käytettiin termiä kotitarvekalastus, tarkoittaen sellaista kalastusta, jossa saalis käytettiin kalastajan omassa taloudessa, ja sillä oli toimeentulon kannalta suuri merkitys. Kalaa riitti perheessä hyvin ruuaksi, ja ajoittain sitä saattoi olla pieni määrä jopa myyntiin asti.

Kiistelyä lohen omistajuudesta eli kuka saa pyydystää lohta, on käyty keskiajalta lähtien, jolloin Suomi oli osa Ruotsin kuningaskuntaa. Nykyisin vilkkaan keskustelun eri näkökulmiin pääsee tutustumaan halutessaan myös sosiaalisen median kautta. Koska aiheeseen liittyy paljon epäselvyyksiä, maa- ja metsätalousministeriö laati vuonna 2019 selvityksen, jossa käytiin läpi valtion regaalioikeutta, eli yksinoikeutta lohen ja taimenen pyyntiin Pohjois-Suomessa, sekä valtion edellytyksiä luopua tästä oikeudestaan tulevaisuudessa3.

Mielestäni selvityksestä saa hyvää materiaalia lohen tulevaisuutta koskevan keskustelun jatkamiseen. Ja on hienoa, että myös valtio kykenee reflektoimaan eli arvioimaan omien toimenpiteidensä merkitystä ja muutostarpeita oikeushistoriallisesta näkökulmasta.

Enemmän kuin lohen omistajuutta ja siitä saatavaa taloudellista hyötyä – että kuuluuko Kemijoen lohi alueella eläneille metsäsaamelaisille, vesialueita omistaneille talonpojille, yksityisiä rantapatoja ja -verkkoja pitäneille kalastajille vaiko valtiolle – ajattelen, että tärkeintä on lohen ja myös muun kalaston itseisarvo ja biodiversiteetti. Käyttöarvon lisäksi poliittisia päätöksiä tehdessä tulisi ottaa huomioon myös olemassaoloarvo, jotta lajien ja niiden elinympäristöjen säilyminen voidaan parhaiten turvata tulevaisuudessa.

Lohen poliittisesta puolesta mielenkiintoisen näkökulman aiheeseen tuo Ville-Aarne Nordberg tuoreessa yhteiskuntatieteen tutkimuksessa4, jossa hän analysoi lohen merkitystä poliittisen ja alueellisen identiteetin rakentajana. Viitaten Tornio-Muonionjokilaaksossa tekemiinsä haastatteluihin Nordberg havaitsi, että lohi ja lohenkalastus tukivat niin alueellisten kuin poliittistenkin identiteettien rakentumista. ’Nämä taas johtavat erilaisiin vaikuttamiskeinoihin ja pyrkimyksiin sekä rakentavat myös käsitystä omasta elinympäristöstä ja sen eroavaisuudesta muihin alueisiin.’

Oman perintöni Kemijoen lohesta ja lohenpyynnistä olen saanut aineettoman perinnön muodossa, mikä tarkoittaa lukuisia tarinoita, jotka ovat kulkeneet perheessämme sukupolvelta toiselle. Nämä tarinat ovat elävää kulttuuriperintöä, sellaista materiaalia, johon voi perehtyä ilman, että huomio kohdistuisi ensisijaisesti poliittisiin, taloudellisiin tai omistajuutta koskeviin näkökulmiin.

Ympäristösosiologi Outi Auttin5 mukaan tarinat lohesta ovat olleet keskeisiä pohjoisten suurjokien kalastuskulttuurissa: paikalliset asukkaat havainnoivat ja oppivat lohen käyttäytymistä kalastaessaan, ja tulkitsivat ja vertailivat tarinoita ja havaintoja omaan elämäänsä. Ja että ’lohi muovasi paitsi jokivartisten yhteisöjen lohenkalastusidentiteettiä, myös yksittäisten ihmisten käsitystä itsestään. Lohi vaikutti perustavasti ihmisten, perheiden ja sukujen olemisen tapoihin, perinteisiin ja paikkaan kuulumisen tunteeseen.’

Tarinankertomisella on siis voimakas merkitys. Margaret Atwood6 viittaa teoriaan, jonka mukaan tarinan varhaisin muoto on tarina matkasta tämän todellisuuden – tässä ja nyt -todellisuuden, jossa sekä tarinankertoja että kuuntelijat ovat olemassa – ja toisen ulottuvuuden välillä, joka voi olla menneisyys tai esivanhempien tai kuolleiden maailma.

Atwood uskoo, että taiteen ja tarinoiden avulla ihmislaji on kyennyt selviytymään aikojen alusta tähän saakka. Että meille on lajina kehittynyt adaptaatio erittäin pitkän ajan kuluessa, jonka vietimme pleistoseeniajan metsästys- ja keräilykulttuureissa. Tarinat auttoivat selviytymään, muutenhan kyky luoda tai välittää kertomus olisi jäänyt pois evoluutiomme aikana.

Tämä seuraava pieni matka kahden todellisuuden ulottuvuuden välillä ajoittuu perheessämme 1920-luvulle. Kyseessä on tarina Kemijoelta isäni, Veikko Kerättären kertomana, ja sisareni Outi Auttin haastattelututkimuksen yhteydessä tallentamana:

Se oli äiji (isoisä) sitte lähteny käymhän lyhyen reissun tuolla Auttisa, jonku asian takia se oli joutunu olhen yötä sielä. Ja se oli sanonu isälle lähtiissä, että käy siä aamulla kokemassa ne verkot. Niin isähän oli menny tuonne joelle, ja siellä oli ollu kaks lohta. Oliko se ollu poikamies silloin isäki, nii se oli arvellu, että pittää hänenki saaha vähän rahhaa, niin se oli myyä sutassu sen toisen lohen, ja päättäny ettei puhu äijile mithän. Vaan äijivainaja oli tullu sieltä Auttista ja sanonu että – no miten se siellä lohiverkoilla? – Olihan siellä yks lohi, oli. – Eikö ollu kahta?! Kaks niitä oli niitä miestä joitten kans miä viime yönä unissani tappelin.